Where is my Chablis? Making sense of the global shipping crisis

At this point, most everyone in the industry is aware of the current global shipping crisis. Transit times from winery to distributor warehouse have crept to a snail’s pace due to container shortages, blank sailings, and backups at ports of entry. This all means lead times that are 2–3 times longer in comparison to this time last year, and to add insult to injury, we are all paying triple last year’s freight rates for the privilege. How and why did we get into this mess? How does this whole freight business function? Where are things heading? Let’s take a second to break things down.

Shipping goods across oceans in boxes is a centuries-old tradition, and until fairly recently the loading and unloading ships was extremely complicated, expensive, and time-consuming. Visualize pulling thousands of separate sized parcels, all of random textures, markings, and sizes, from small vessels of various size and shape. Does this sound messy, inefficient, and expensive? It was! As we complain about current shipping woes, we might as well throw some gratitude to the invention of the “standardized container” and modern logistics. The standardized container, you know, the 20’ and 40’ boxes that you see on freight vessels, trains, and semi-trucks, is a new phenomenon. This technology was invented by the American trucking industry seventy years ago. The idea was to create a system where a standard-sized “box” could efficiently transfer between purpose-built ships, trains, and trucks. Deemed “standardized shipping,” this development made the movement of inexpensive goods at scale economically possible. The first purpose-built container ships were commissioned in 1956 and carried 68 containers. Ship size gradually grew in each decade, and by the early 2000s, most container ships had a capacity of 17,000 20’ containers.

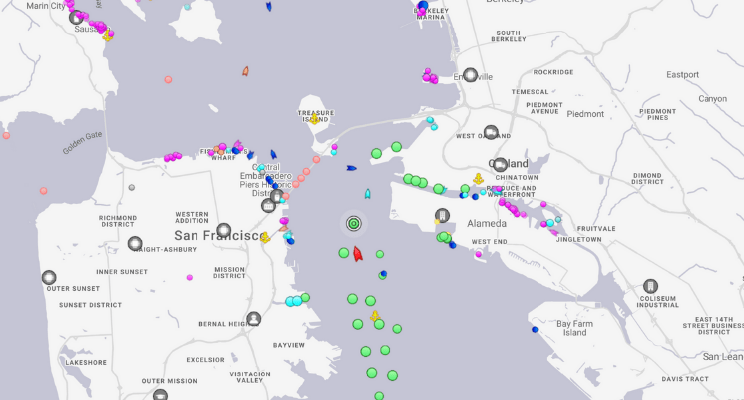

This world of standardized shipping is operated by companies we call “ocean carriers.” Ocean carriers own/operate vessels and offer a consistent menu of routes, which we call “streams” in industry-speak. For example, let’s look at our favorite “stream” here at Grape Expectations. Each Tuesday a vessel leaves Fos-Marseille, and stops at 7 or 8 similar sized ports along the route, in the end dropping our goods off in Oakland. There are a number of separate vessels on this run, they are usually the same size (most are purpose-built for the “stream” in question), and are evenly spaced out so that they make one big circle with one vessel on the “stream,” hitting another port on the route every seven days or so. When this works, it is incredibly efficient and a triumph of modern logistics.

As far as the legal/financial side of things goes, the shipping business works under contract. Companies importing goods can either book freight direct with ocean carriers, or as is customary in our wine industry they can work with firms we call “freight forwarders.” A freight forwarder will negotiate with ocean carriers on behalf of hundreds of importer clients, setting a contract over a twelve-month period where the forwarder will agree to have a specific amount of containers booked onto a specific “stream” each week in exchange for favorable pricing. Wine and liquor are some of the most consistent commodities shipped out of European ports thanks to their unwavering demand abroad, and parties dealing in these goods generally receive low freight prices from ocean carriers as a result. When the world is normal and these contracts work, things are beautiful.

The glory years of this setup described above were those leading up to the Great Recession. Around this time, carriers came up with the idea to build “mega-ships” that could hold over 21,000 20’ containers (visualize that huge vessel that was made famous via being stuck in the Suez Canal), with the thinking that international trade would continue to grow and that there was no ceiling to economies of scale as they relate to vessel size. In came the global financial crisis, and international trade slowed. We ended up with too many ships, too large of ships, and therefore a crisis of excess capacity to a point that the industry saw transocean container prices crashing, dipping under $1,000 per unit in a short time. This resulted in an economic catastrophe for ocean carriers, and many of them went out of business. Surviving ocean carriers organized themselves into three (oligarchic) alliances:

2M: MSC (Switzerland) and Maersk (Denmark) *33% global market share

Ocean Alliance: Cosco (China), Evergreen (Taiwan), CMA CGM (France), OOCL (Hong Kong) *30% global market share

THE Alliance: Hapag Lloyd (Germany), ONE (Japanese), Yang Ming (Taiwan), HMM (Korea) *20% global market share

We know what you are thinking — What happens when you have an industry controlled by just three parties, a global pandemic, and an arbitrary temporary pause to a global trade war? You guessed it…you get today’s global freight crisis!

Yikes — Let’s dig in, shall we?

Covid meant a world stuck at home. When people in the United States and Europe are locked in their houses they cannot spend money on travel, restaurants, and experiences. This means an increase in self-entertainment via buying consumer goods, most of which are manufactured in China and shipped on containers. With less demand for goods coming back to China from Europe and the United States, the equilibrium in global supply lines became unbalanced.

Actual physical container shortages added another layer of mayhem to this mix. Until recently, ocean carriers manufactured their own physical containers. Nowadays, containers are built by separate companies. These container building firms (most of them based in China) suffered manufacturing delays due to reduced staffing due to Covid, meaning fewer actual containers to put goods into. With fewer new containers being constructed, and empty containers shipping back to China we had a big problem. The result was either wine sitting at wineries in search of a physical container, or even more frustrating, wine-filled containers being routed back from “blank” vessels whose operators left port without cargo, knowing that they could make more money shipping back empty containers that could quickly be refilled with more Chinese consumer goods, which could be quickly shipped back to Western states to fill quickly depleting retail shelves and Amazon warehouses.

Remember the bit about wine being a “staple” in terms of product booked on all of these vessels? The Biden Administration’s four-month “tariff pause” created an unprecedented surge in wine bookings, and more importantly in bookings made by European industrial manufacturers. The manufacturing segment had more skin in the tariff-avoidance game than the wine segment (tariffed BMW’s are more expensive and problematic than tariffed bottles of Chablis), and the manufacturing industry offered crazy dollars to ocean carriers in exchange for guaranteed bookings. As a result, “wine” containers were squeezed out and this has been another cause of rejection at the port.

What about the vessels themselves? If everything is delayed, can’t all the vessels in the “stream” push the pedal to the metal and charge towards the port faster? This used to be the case — A vessel that was behind schedule would go from a standard 20-knot speed to 27 knots to “catch up.” The new mega-sized ships that rule the roost now were designed with fuel efficiency in mind and cannot move faster than 17 knots. This adds an extra week or two to transit times, and limited speed means “catching up” is no longer an option as it was in freight crises of prior eras.

These long transit times hurt smaller/less-capitalized importing businesses the hardest, as three month freight times mean that in most cases winery bills will be due prior to product arrival, rather than a month or two after the company in question has had the chance to sell the product — A cash flow nightmare! If there was ever a time to support independent wineries and import companies, now is that time. Our approach at Grape Expectations is to shower you with crazy offers that you can’t refuse as soon as product lands in our warehouse. You can call this what you wish…we will call it making lemonade from lemons, for YOUR buying pleasure.

We hope this isn’t too negative a breakdown — We simply want to give you a quick (and realistic) look at the situation at hand. All of us in the industry have been hard at work booking loads far in advance, and while we are in for a rocky road as an industry, we expect to make it out of this just fine in the end. Let’s give a toast of gratitude to an international freight system that works miraculously well most of the time, and let’s also raise a glass to the hope that this difficult situation resolves itself by the end of 2021.